Different Levels of Abstraction

The ability of abstracting should be the most fundamental skill a developer should have, and I can't emphasise this enough. By abstracting, we can escape from the overwhelming seemingly irrelevant details to a solution that could solve all the problems at one go.

The ability of abstracting should be the most fundamental skill a developer should have, and I can't emphasise this enough. By abstracting, we can escape from the overwhelming seemingly irrelevant details to a solution that could solve all the problems at one go.

However, since every abstraction omits some details and emphasises some other features, sometimes it can block us from understanding the problem (I guess our brains prefer tangible things more). And that's when examples jump in for help. In other words, during a creative process, either coding or designing we, on the one hand, need to extract concepts out of concrete examples, on the other hand, we need to exemplify concepts we extracted back to instances. Bret Victor made a great metaphor about this process as going up and down a ladder - you need to go up to a higher level to have some overview and then back to the ground to test it. Only by combining those two you can understand the problem better and come up with better solutions.

Another interesting fact about abstraction is it has layers. Once we get rid of all the clutter details on the ground and have higher-level concepts, those abstractions turn to be the new details, and we can again build abstract concepts on top of them. That's why we can use JavaScript or Python to just resolve business problems without knowing the register address or the length of machine instructions, or how the memory is allocated or freed.

I know it sounds abstract already, but bear with me and have a look at a concrete example.

Some context

In this article, I'm going to describe some patterns and refactor techniques by refactoring the test suite of a simulated project (using cypress). I will talk about some regular refactor tricks and nothing major, and I believe by seeing how to analyze and rewrite some test cases from working code to concise and easy to understand/modify is worthwhile, and hopefully can be fun as well. And I hope you can enjoy it.

It simulated a project I've been part of last year. From the business perspective, the difficult of all the business rules and logic is mediocre, but technically there are lots of details that deserve some retrospections. The UI test suites in the project, after several rounds of refactoring, eventually reached somewhere I'm pretty happy with, and it has been applying patterns we're going to talk about in this article.

The simulation here, however, is a service called Questionnaire, it uses some calculation engine at the backend to return some best-fit offers to the user, by asking some questions like roles, skill levels, technical stack, project preferences and so on. I'll leave the recommendation system in the backend along and only focus on data collecting in this article.

Note that some of the questions are dynamic. For instance, if the user answered A for question Q1 then the following question could be Q303. And if they answered B instead, the following one will be Q1024. Which means there are many alternative paths in the UI, and each path is equally important(and each test should walk the path thoroughly until the result is calculated).

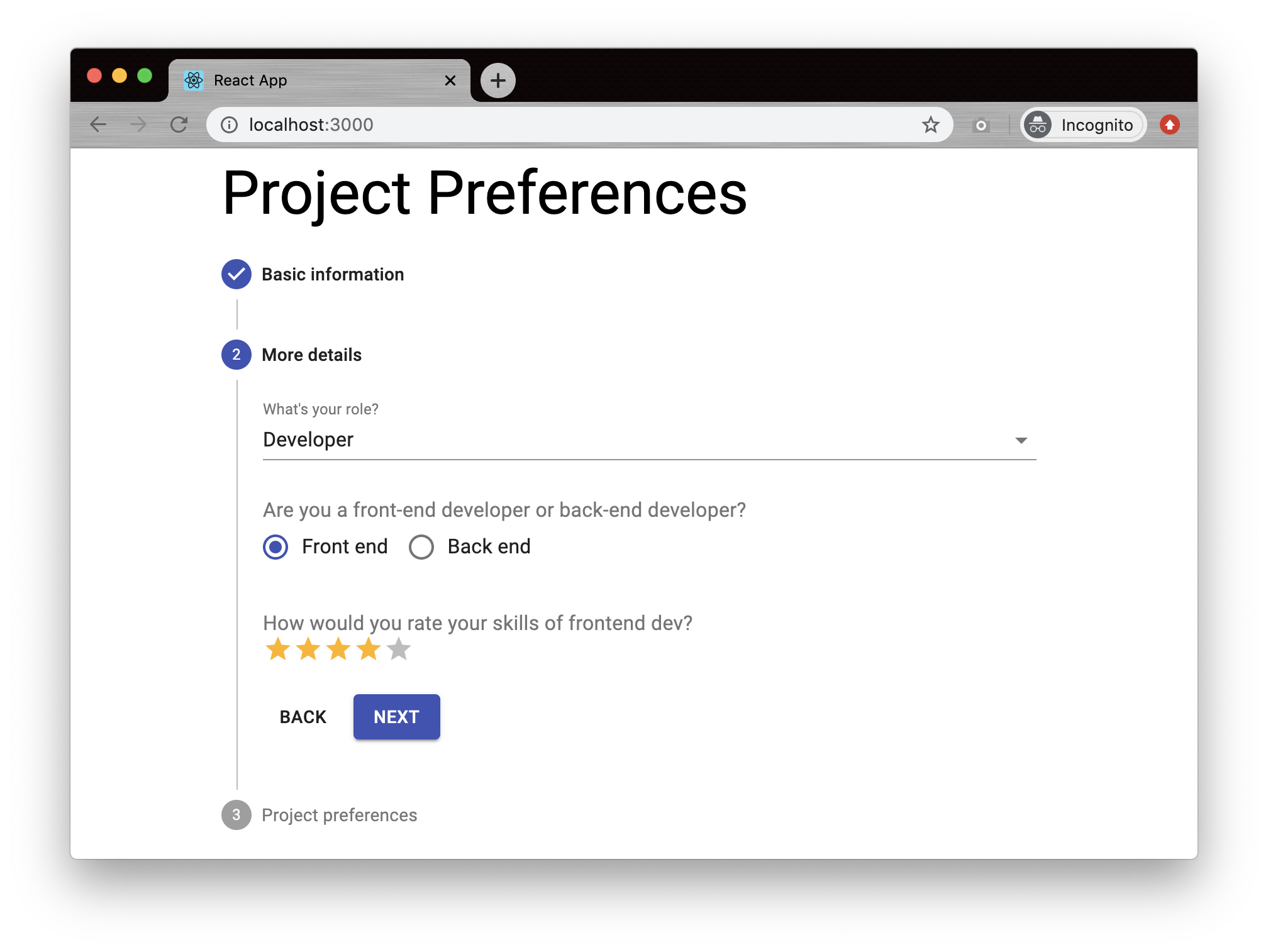

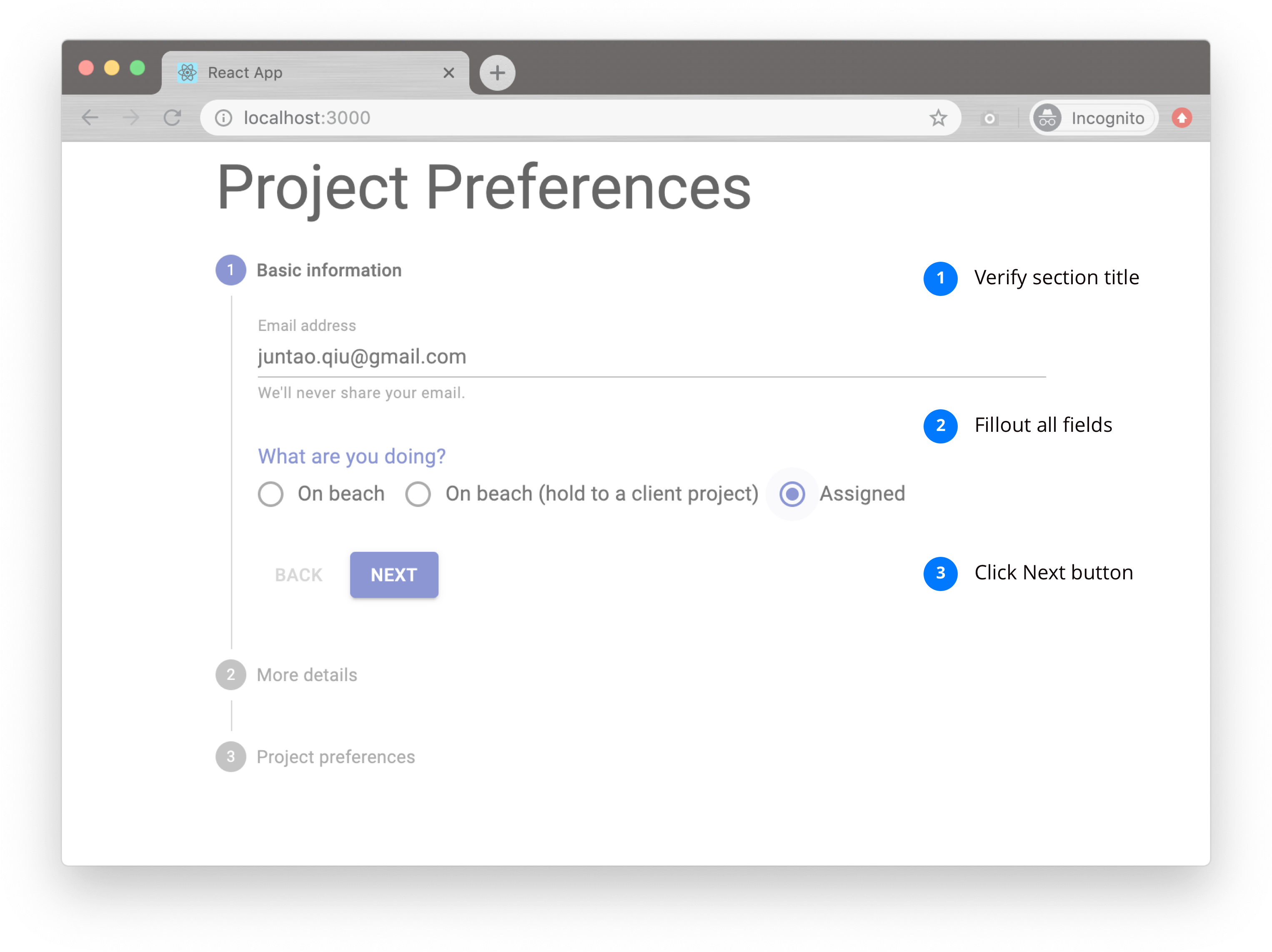

As you can see from the UI above, the Questionnaire has 3 steps, while in the real-world scenario, it could be 10+ steps, and each step has one or more questions. Some questions may depend on the answers in previous steps. Once all the required fields are collected, the user can proceed by clicking the next button.

Abstract 101 - function

From a functional test's point of view, treating each step as a standalone unit is reasonable. Each step has a few similar things to do:

- Verify the step title

- Fill out all the mandatory fields

- Click the Next button

We can test the first Step by using cypress APIs (let's assume all the data- attributes are all in-place already in the product code):

it('Verify the basic information section', () => {

cy.get('[data-test="step-title"]').contains('Basic information');

cy.get('[data-test="email-address"] input').type('juntao.qiu@gmail.com');

cy.get('[data-test="assignment"] input[value="assigned"]').check();

cy.get('button[data-test="next-button"]').click();

});So the second one is pretty similar: using selector to locate element on the page, and if an element is found we can simulate some user actions by cypress API:

it('Verify the details section', () => {

cy.get('[data-test="step-title"]').contains('More details');

cy.get('[data-test="ps-role"]').click();

cy.get('[data-value="dev"]').click();

cy.get('[data-test="developer"] input[value="frontend"]').check();

cy.get('[data-test="rating"] [for="rating-4"]').click();

cy.get('button[data-test="next-button"]').click();

});If you compare the code literally, almost each line is unique, but you can feel there are some sort of duplications. And demolishing those duplications could improve the readability a lot. The easiest way to do this is extract function, for example, extract verify step title and click next button to respective functions:

const checkStepTitle = (title) => {

cy.get("[data-test="step-title"]").contains(title);

}

const goToNextStep = () => {

cy.get("button[data-test="next-button"]").click();

}Then the test is simplified a bit like:

it('Verify the basic information section', () => {

checkStepTitle("Basic information");

cy.get('[data-test="email-address"] input').type('juntao.qiu@gmail.com');

cy.get('[data-test="assignment"] input[value="assigned"]').check();

goToNextStep();

});

it("Verify the details section", () => {

checkStepTitle("More details");

cy.get('[data-test="ps-role"]').click();

cy.get('[data-value="dev"]').click();

cy.get('[data-test="developer"] input[value="frontend"]').check();

cy.get('[data-test="rating"] [for="rating-4"]').click();

goToNextStep();

});You will feel there are some other duplicated code, and if you blur the details you can see the similarity:

When we extract all the cypress actions into a function:

const fillOutBasic = () => {

cy.get('[data-test="email-address"] input').type('juntao.qiu@gmail.com');

cy.get('[data-test="assignment"] input[value="assigned"]').check();

}And then define a template function to perform the following actions:

- Verify step title

- Fill out the mandatory fields

- Click next button

const verifyStep = (title, verifier) => {

checkStepTitle(title);

verifier();

goToNextStep();

}By doing that our test can be simplified further into:

it("Verify the basic information section", () => {

verifyStep("Basic information", fillOutBasic);

});And as well as the second one:

it("Verify the details section", () => {

verifyStep("More details", fillOutDetails);

});Abstract 102 - Simplify a bit more

As you can see above there are several branches for step 2: for developers, there are 3 questions required and for QA/BA there is only 1 mandatory question. We need more test cases to cover each branch:

const fillOutDetailsForDev = () => {

cy.get('[data-test="ps-role"]').click();

cy.get('[data-value="dev"]').click();

cy.get('[data-test="developer"] input[value="frontend"]').check();

cy.get('[data-test="rating"] [for="rating-4"]').click();

}

const fillOutDetailsForQA = () => {

cy.get('[data-test="ps-role"]').click();

cy.get('[data-value="qa"]').click();

}

const fillOutDetailsForBA = () => {

cy.get('[data-test="ps-role"]').click();

cy.get('[data-value="ba"]').click();

}Because of those clutter/detailed code, plus all the cypress API like cy.get stuff make it difficult and indirect to understand the purpose behind each line of code. If we can somehow get rid of those noises, the clearness of the test could improve to a new level.

For example, if we have a group of APIs like following to isolate all the DOM details:

const select = (selector, value) => {

cy.get(`[data-test="${selector}"]`).click();

cy.get(`[data-value="${value}"]`).click();

}

const checkbox = (selector, value) => {

cy.get(`[data-test="${selector}"] input[value="${value}"]`).check();

}Then function fillOutDetailsForDev could be rewrite like:

const fillOutDetailsForDev = () => {

select("ps-role", "dev");

checkbox("developer", "frontend");

rating("rating", "4");

}And fillOutDetailsForQA turns into:

const fillOutDetailsForQA = () => {

select("ps-role", "qa");

}Although their amount of code is pretty similar, what we did here is separate business/test logic and the underlying cypress DOM APIs. If in the future we have to upgrade or change the UI library in product code, we don't have to touch anything in test logic above. Only the implementation of select/checkbox needs to be updated.

Exemplify 101 - inline

But if we look closely enough at functions like fillOutDetailsForDev and fillOutDetailsForQA extracted above, we can see that we kind of lose some flexibility. These named functions locked some actions down, and we may need more and more functions for different scenarios. Probably the anonymous functions fit more here. For example if we inline those fillOutDetailsForDev into anonymous function:

it("Verify the details section for developer", () => {

verifyStep("More details", () => {

select("ps-role", "dev");

checkbox("developer", "frontend");

rating("rating", "4");

});

});

it("Verify the details section for QA", () => {

verifyStep("More details", () => {

select("ps-role", "qa");

});

});I suppose the test cases above are much better comparing to those who strongly tied to cypress API, and now each line of code has a more precise purpose, they're saying what needs to be done, other than how to do it.

And we can take a close look at a complete User Journey now in a test case (remember for the sake of simplicity only 3 steps here, but could be more in a real-world project).

it("Verify the details section for developer", () => {

verifyStep("Basic information", () => {

input("email-address", "juntao.qiu@gmail.com");

checkbox("assignment", "assigned");

});

verifyStep("More details", () => {

select("ps-role", "dev");

checkbox("developer", "frontend");

rating("rating", "4");

});

verifyStep("Project preferences", () => {

checkbox("expectancy", "frontend");

});

});If you feel the same way as I am for those 3 lines of ```identical"` duplicated code, let's try another approach to demolish these duplications.

Abstract 201 - code and data

In most modern functional programming languages, the boundary between data and code is blurring, by using built-in functions like eval/apply developers can easily convert those two. Even if you can not implement code is data in your code, at least you can extract those volatile pieces into data or config(such as selector, question sequence definition, rearrange the order of questions etc), and ensure the stable part is treated differently as a framework.

For instance, in the scenario Verify the details section for developer discussed above, we can probably rewrite it as:

steps.forEach(step => {

verifyStep(step.title, step.verifier)

});in which the steps is defined as:

const steps = [

{

title: 'Basic information',

verifier: () => { /*input, select, checkbox*/ }

},

{

title: 'Basic information',

verifier: () => { /*input, select, checkbox*/ }

},

];This way, we can separate those logic into a static config. Of course, the verifier is still dynamic (defined as a function). If we can introduce a mechanism to convert things like checkbox("expectancy", "frontend") into a static config, we can claim that data and code are completely split, and the benefit of it is that we don't have to touch any code if a User Journey need to be updated.

A User Journey

Let's say we need to test a user journey defined as following steps:

- A user input email address

- The user selects

beachas the current project - The user rates him/her as a medium-level front end developer

- And he/she wants to try

SREin the coming engagement

And we can describe those input sequence as the following format:

const steps = [

{

"title": "Basic information",

"fields": [

"input:email-address:abruzzi.dev@gmail.com",

"checkbox:assignment:assigned",

]

},

{

"title": "More details",

"fields": [

"select:ps-role:dev",

"checkbox:developer:frontend",

"rating:rating:4",

]

},

{

"title": "Project preferences",

"fields": [

"checkbox:expectancy:frontend",

]

}

];And if we have a mapping function to interpret fields above as operation functions we extracted earlier, we can then execute those config eventually:

const executeCypressCommand = (field) => {

const [type, selector, value] = field.split(':');

switch (type) {

case 'input': return input(selector, value);

case 'checkbox': return checkbox(selector, value);

case 'select': return select(selector, value);

case 'rating': return rating(selector, value);

default: return null;

}

}That means fields definition:

"fields": [

"input:email-address:abruzzi.dev@gmail.com",

"checkbox:assignment:assigned",

]is translated into:

input('email-address', 'abruzzi.dev@gmail.com');

checkbox('assignment', 'assigned');and at runtime, input and checkbox will be interpret into underlying cypress instructions:

cy.get('[data-test="email-address"] input').type('abruzzi.dev@gmail.com');

cy.get('[data-test="assignment"] input[value="assigned"]').check();This way, when a new User Journey is needed, the only change required is to add a json file. The json will be loaded and interpreted, and eventually be able to run in browser like so:

And it becomes effortless to add/modify/delete steps in any journey, and it's super easy to make sure tests are synced with the UI of product code as well.

If the idea of external all the test cases into json files looks radical, only utilise the extracted utility functions can improve the readability and reduce the dependence to the underlying DOM APIs.

verifySection('Basic information', () => {

input('email-address', 'abruzzi.dev@gmail.com');

checkbox('assignment', 'assigned');

});

verifySection('More details', () => {

select('ps-role', 'qa');

});Abstract 202 - User cases

We've already done a lot, from extracting reusable functions to a highly abstracted, domain-specific API, and those API in large extent aligns with the language shared by both developers and people who write tests.

If we inspect those test cases:

it('explore journey for developers', () => {

runJourney(developerJourney)

});

it('explore journey for qas', () => {

runJourney(qaJourney);

});You can find that they are duplicated code in some way, do you still remember the last refactor we did above for steps? A similar forEach can remove those duplications.

journeys.forEach((journey) => {

it(journey.title, () => {

runJourney(journey);

});

});No matter how many User Journeys we have, we don't have to change code any more. For loading different journeys, it's pretty straightforward to use import/export from ES6:

import {journey as qaJourney} from "./qa";

import {journey as baJourney} from "./ba";

import {journey as devJourney} from "./developer";

import {journey as devBeachJourney} from "./developer-on-beach";

const journeys = [

qaJourney,

baJourney,

devJourney,

devBeachJourney,

];

export default journeys;Because every journey is a plain static JSON, for any further business logic changes, we only need to update those static files without worrying about regressions of the framework code.

Summary

In this article, I introduced a few how to abstract methods/patterns through refactoring a test suite, and at the end, we isolated all the frequently-changing parts into separate `json's, and make the potential change easier and more centric.

We have done several forms of abstractions: from the fundamental way of abstract duplicate code into functions to wire logically related code into small functions and then introduce a high-order function to do a higher-level abstraction. Additionally, when some statements with similar structure appear, we can use data+each/map to separate code and data.

Just as the metaphor Bret Victor talked about, the whole process may be not straight and could spiral in most cases. We rarely can see how the code will be at the very beginning, and in the middle of refactoring, there will be a lot of back and forth. Those back and forth is not only inevitable but also indispensable. In most cases, a good refactor needs a lot of attempts in different directions and several rounds to make the code into an ideal state. But you have to be very careful of this ideal state because it's normally unstable, and once the next breaking change comes, we have to apply the same principles again to abstract and exemplify in different levels to adopt these changes.